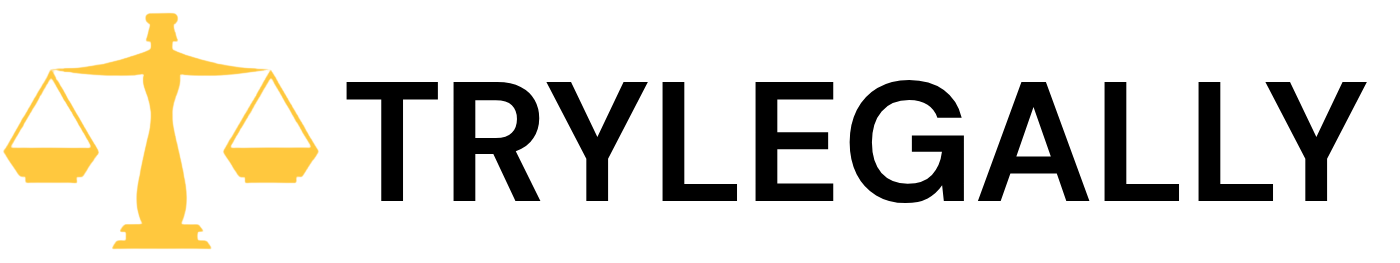

The arrival of Generative AI (GenAI) has been described as a transformative moment for the legal industry—comparable to the advent of the steam engine, the telegraph, or the smartphone. While this technology promises to revolutionize how law firms operate and how legal work is staffed, it also introduces a minefield of ethical risks.

For legal practitioners, the question is no longer if they will use AI, but how they can use it without running afoul of professional obligations.

Understanding the Tool: It’s Not Just a Search Engine

To use GenAI ethically, lawyers must first understand what it is. Unlike traditional research tools that retrieve known data, Generative AI models (like Large Language Models) are predictive engines. They are trained on massive amounts of data to predict the next likely word in a sequence based on probability.

Because these models generate new content rather than just retrieving existing content, they suffer from specific flaws:

Hallucinations: The models can “make stuff up,” including falsifying case law or facts.

Bias: Because they are trained on the internet, they may reflect inherent human or historical biases.

Inconsistency: Asking the same question three times might yield three different answers.

The Ethical Guardrails: ABA Opinion 512

In July 2024, the American Bar Association released Formal Opinion 512, which has become the leading guidance for lawyers using GenAI. Along with various state rulings and local court orders, this opinion highlights several non-negotiable ethical duties.

- The Duty of Competence (Rule 1.1) : Lawyers are not expected to be computer scientists, but they must have a firm grasp of how the technology works. You cannot simply open a tool and start using it; you have an obligation to understand what the tool does, what it doesn’t do, and the specific risks associated with it.

- Independent Professional Judgment: Perhaps the most critical rule is that AI cannot replace a lawyer’s independent judgment. There are currently hundreds of reported decisions where pleadings or evidence were submitted based on AI hallucinations because the attorney failed to verify the output. Attorneys must independently validate every citation and factual assertion generated by AI. Under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 11, the attorney signing the document is responsible for its content, regardless of whether a human or a machine drafted it.

- Confidentiality and Privilege: One of the biggest traps for the unwary is the issue of confidentiality. Many public GenAI tools are not secure; when you input a prompt, that information may become public or be used to train the model. Uploading a client’s sensitive trade secrets or a confidential deposition transcript into a public chatbot could constitute a waiver of privilege. Lawyers must distinguish between public tools and private, enterprise-grade versions that sit behind secure firewalls and do not retain data for training.

- Billing and Fees: GenAI can drastically reduce the time required for tasks. For example, a task like summarising a 144-page complaint, which might take an associate 10 hours, could potentially be done by an AI engine in minutes. Ethically, who gets the benefit of that efficiency? The guidance suggests that if an engine allows a task to be done in substantially less time, the client must receive the benefit of the doubt and be charged less.

Practical Use Cases and the Future

Despite the risks, the utility of these tools is undeniable. Current effective use cases include:

E-Discovery: Sorting relevant from non-relevant documents, identifying privilege, and creating chronologies.

Summarisation: Digesting depositions or long pleadings instantly.

Drafting: Assisting with contracts and initial drafts of briefs.

Looking forward, the industry is moving toward “Agentic AI” specialised agents designed to execute specific workflows, such as performing an early case assessment by combining research, summarisation, and chronology tasks automatically.

Conclusion: Evolution, Not Replacement

A common fear is that AI will replace lawyers. The consensus among experts is that this is unlikely. While AI will change staffing models and increase productivity, clients ultimately hire lawyers for their independent legal judgment—something a machine cannot replicate.

To stay safe, firms should adopt clear policies, invest in training, and ensure that every piece of AI-generated work is rigorously vetted by a human professional. As the technology matures, it will make lawyers better at their jobs, but only if used with a clear understanding of the “great responsibility” that comes with such “great power”.